Big Tech Capex and Earnings Quality

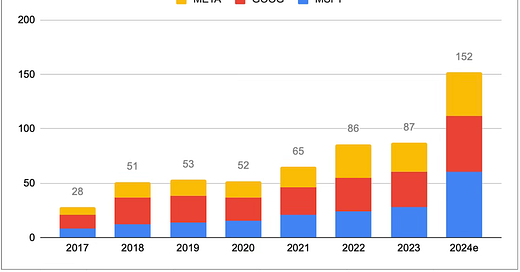

The capex spending at MSFT, META, GOOG will eclipse $150 billion this year alone. These businesses are much different than they were 5 years ago with perhaps different return on capital profiles.

These companies are very different than they were 5 years ago:

They once were very capital light, able to grow with little marginal costs. Now they are becoming much more capital intensive.

Capex is not only growing larger, but the rate of growth is set to accelerate this year as they invest in the AI boom. Combined capex at MSFT, GOOG and META is set to grow around 70% in 2024. As a percentage of sales, capex will grow from 13% of sales in 2023 to around 20% in 2024.

While most investors are aware of the growing capex requirements, I think many might be under appreciating how capital intensive these companies are becoming. Part of the reason for this is because these massive investments don’t immediately hit the income statement. They instead get expensed as depreciation over the useful life of the asset (e.g. the cost of a computer server in a data center gets expensed over 5-6 years).

Of course, this is the normal result for a company that is growing and investing in its future, but what is eye-catching about the big tech companies is the sheer size of this growth in dollar terms and the increasing rate of change of the growth: Capex is now over 3 times depreciation expense.

Last year numbers (ttm) and management guidance for 2024:

MSFT

15b depreciation

40b capex

Guide to ~60b+ this year

GOOG

13b depreciation

38b capex

Guide to ~50b this year

META

12b depreciation

27b capex

Guide to 35-40b this year

This spending hasn’t yet hit the income statement, but it will in the next few years as depreciation expenses are set to triple in the coming years as D&A catches up with today’s capex spending.

And this depreciation expense will keep rising until capex growth stops, which will happen at some point, but doesn’t sound imminent. From their most recent earnings calls:

META:

We anticipate our full-year 2024 capital expenditures will be in the range of $35-40 billion, increased from our prior range of $30-37 billion as we continue to accelerate our infrastructure investments to support our artificial intelligence (AI) roadmap. While we are not providing guidance for years beyond 2024, we expect capital expenditures will continue to increase next year as we invest aggressively to support our ambitious AI research and product development efforts.

GOOG:

Our reported CapEx in the first quarter was $12 billion, once again driven overwhelmingly by investment in our technical infrastructure, with the largest component for servers followed by data centers. The significant year-on-year growth in CapEx in recent quarters reflects our confidence in the opportunities offered by AI across our business.

We are very cognizant of the increasing headwind we have from higher depreciation and expenses associated with the higher capex.

MSFT:

We expect capital expenditures to increase materially on a sequential basis driven by cloud and AI infrastructure investments.

Bottom line: the other Big Techs are getting far more capital intensive than they have in the past. Their FCF is currently lagging net income because of the large capex, and this will eventually flow through to much higher depreciation charges in the coming years.

This is not necessarily worrying — if the returns on these investments are good, then sales growth will be able to absorb these much higher expenses. But this is not a sure thing, so I like to use P/FCF metrics as I think a large majority of the assets they’re investing in will need to be replaced. This means the capex levels we see currently could be recurring. So, while the P/E ratios range from 25 to 35, the P/FCF ranges from 40-50.

Again, if the investments are able to earn good returns, then profit margins will remain intact, but one thing to notice is FCF margins (while very strong) have not kept up with GAAP profit margins: e.g. at MSFT, FCF margins have declined slightly from 28% to 26% over the last decade while net margins have expanded from 25% to 36%, leaving GAAP profit margins far in excess of FCF margins. Eventually, as growth slows these margins will tend to converge as depreciation “catches up” to cash capex spend. Whether net margins come down or FCF margins move up simply depends on the returns on capital earned and the growth it produces.

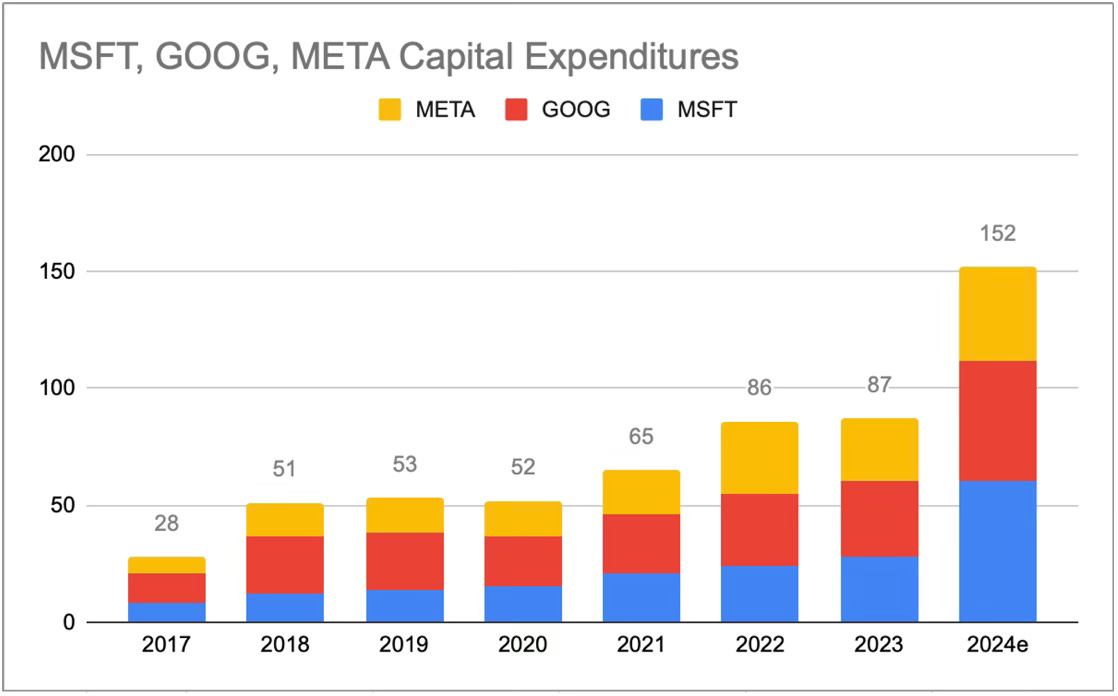

I’m not predicting a poor result, but I’m mindful of how difficult it will be given how different the companies are today. They used to grow with very little capital invested, but now they have a mountain of capital to deploy, which is obviously much harder at 7 times the size:

I included Amazon in this table because I think it’s very interesting that even Amazon was relatively capital light as recently as 2017. Amazon has invested in its warehouses and all four of these companies have ramped up spending on cloud infrastructure and tech hardware to compete in AI.

The returns on capital have been extraordinary looking through the rearview:

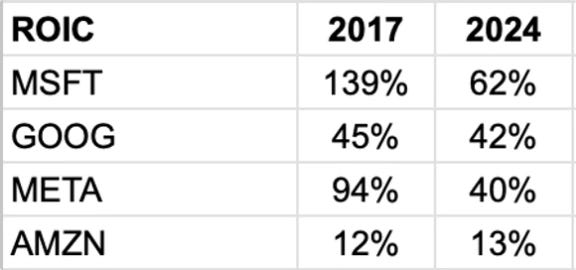

If we include intangible investments (which I include because they are part of the capital allocation strategy at these companies), the incremental returns over the past 7 years have been great:

With three quarters of a trillion dollars of capital invested, I think it’s going to be a much more difficult task over the next decade to earn returns anywhere near as good as they were. The returns on capital are what lead to earnings growth. (See this series I wrote on the Importance of ROIC for more on how I calculate and think about returns on capital).

Without earnings growth, stockholders will need to see contribution from either the P/E multiple or capital returns (see 3 Engines post). With P/E ratios quite high and thus capital returns quite modest, my conclusion is that while these companies are great, the returns owners get depend on current price of the shares and the future returns on capital earned.

Maintenance vs Growth Capex

Investors and management teams are very excited about the massive opportunity in AI, which begs the question: shouldn’t these companies be investing for this bright future?

My view is somewhat different than most of the investors I speak to. It depends on the returns on capital generated, but given the nature of these companies and the fast changing technology landscape, I don’t really think these companies have much of a choice. Thus, I think growth and maintenance capex are one and the same. It’s very difficult for even the management teams to delineate between what capital is needed to keep their position and what is needed to grow. I think growth and capex in these particular businesses is fungible. Is the capital Meta invested to roll out Reels a few years ago maintenance or growth? It certainly led to growth, but if they didn’t do it their network effects almost certainly would have been impaired. Is Google’s investment in data centers needed to build out its AI search considered maintenance or growth? It has fueled growth but if they don’t invest, their search engine might eventually get left behind to ChatGPT or some other new alternative. Same goes for their cloud investments and their AI spending today. As Kramer once said: “the muscle must grow, or die”.

I think the same applies for these big tech business models. They’re either growing or they’re losing out to some other competitor. I don’t think it makes sense to parse out what is growth vs maintenance: it’s all necessary for survival long-term. The value we see as owners will come from what is left over (the free cash flow) plus any growth that materializes.

This is why it’s important to look at FCF (after all capex) and not just reported earnings. I think all of the tangible assets that the company is investing in will likely need to replaced over time (much of it over 5-6 years as tech hardware lifespans quickly depreciate).

The capex is both growth and maintenance at the same time.

Investing For Growth and Determining ROIC

Walmart was free cash flow negative for the first 3 decades of its life as it was building out new stores funded with additional debt. The same went for Home Depot. These companies and many like them retained large portions of their earnings to invest for much larger earnings streams later. Investing for growth is obviously a great thing when ROIC is high.

But, this is where I am somewhat cautious on big tech currently. With companies like HD, WMT, ORLY, FAST and perhaps current growth companies like FND, I can understand and measure the capital allocation. It’s simple to see how HD was earning 30% cash on cash returns opening new stores, but I don’t think anyone (including management) yet knows what the returns on the $150 billion of investments that these three companies will spend in 2024. They are optimistic, but it’s not clear cut to me.

Think about how much profit needs to be generated annually to earn acceptable returns on this capex: a 10% return would require $15 billion of additional after tax profits in year 1. As Buffett points out, if you require a 10% return on a $150 billion investment but get nothing in year 1, then you’d need $32 billion in year 2, and just one more year of deferred returns would require a massive $50 billion profit in year 3.

This is somewhat oversimplified because some of this return might in fact come in the form of maintaining current earnings (e.g. maintenance capex). But to my point above, I don’t think it matters to segregate the two. The point is that each dollar invested needs to earn adequate returns in order to create value.

What’s staggering is that the above is the return needed to earn 10% on just one year’s worth of capex. Even if we assume that capex growth slows from 70% this year down to 0% in 2025 and stays there, MSFT, GOOG and META will invest an additional $750 billion of capital over the next 5 years!

Like the internet, AI is a complete game changer. But the companies that invested to build out the internet were not always the long term winners. Shareholders only benefit if the returns on those investments end up creating value. And I say this as a (perhaps circumspect) long-term owner of MSFT and GOOG. I continue to love these businesses, but given the increasing valuations placed on current and future earnings that might be harder to come by, I’ve begun trimming my investments in favor of ideas I think offer more potential. I still expect these companies to perform well and perhaps the stocks continue to do well even from these levels. But as investors, we deal in probabilities and have to manage risk, and these businesses are much different than they were just five years ago with much greater capital needs and higher valuation levels, which simply changes the odds in my view.

3 Engines

If these companies can grow at 10% annually for the next decade (no small task given the larger base), that’s a 2.6x return from the growth engine. If the P/E ratio falls from 30 to 20, then the stock returns fall to just 5.6% per year over a decade, with dividends and buybacks adding a couple points to this return. You can never be precise with long-term assumptions, but I think it’s likely that mid to high single digits will be difficult for these stocks to exceed over the next decade.

In short, I view these stocks as more fairly valued today. Great businesses, but perhaps not great investments. Like Charlie Munger said: it’s important to not forget what we’re trying to do. Our goal isn’t to pick the best businesses, but to pick the best investments. I noticed Buffett has started to sell a chunk of his investment in Apple. I think he might view AAPL in a similar way — a great business without a doubt, but perhaps a lesser quality investment than it was 7-8 years ago. That’s my general feeling with a number of these world beating companies that I continue to admire and will continue to root for.

I’m very interested to watch it play out.

In the meantime, there are lots of interesting things to work on currently. Investing is about managing risks and opportunity costs. In a reply to an Apple question, Buffett referenced Ben Graham who said at one price, a company can be a great investment and at another price a poor investment. I don’t think Apple or any stock mentioned here will be a poor investment. In fact I think they could still do well. But the prices have changed and I’ve been finding a number of other ideas that I think offer better safety of principal and higher return potential.

I’m excited about continuing to investigate new opportunities while also watching how companies manage these interesting times. And I’ll share more thoughts as I have them on both general topics as well as some of our investments.

Thanks for reading!

John Huber is the founder of Saber Capital Management, LLC. Saber is the general partner and manager of an investment fund modeled after the original Buffett partnerships. Saber’s strategy is to make very carefully selected investments in undervalued stocks of great businesses.

John can be reached at john@sabercapitalmgt.com.

Have you considered "The New Goliaths" by James Bessen? Seems like moats are being strengthened.

Companies have personalities like human beings. So, if you are an organization that was born in the 70s or early 80s, and have gone through a crisis or two, that memory is seared in the persona of the organization and how they allocate capital. You can put companies like Microsoft, Oracle, Apple in that genre.

Then you have those that only saw interest rates go one way (AMZN, META, GOOG, CRM) and they are only just learning the discipline of capital allocation, albeit reluctantly. I worked for four of them and as an employee you can totally feel the mindset. The famous one was Oracle where margins ruled supreme, and everyone knew management would gladly sacrifice revenue to keep margins. If you worked at CRM, you asked "what margins?"

I will make two interesting observations of this capex vis-a-vis internet build out:

1) How concentrated this AI capex cycle is and outside of a dozen companies, the rest can hardly afford it.

b) Not everyone needs AI Data center, and even if you do, you going to use a fraction of it. That means there is a high likelihood of a hiccup, and these investments can easily be put on hold.