Thoughts on Ben Graham's "Unpopular Large Caps": A Still-Effective Strategy

Graham's view on how large caps can get mispriced, a time arbitrage investment approach that worked for Graham and still works today

One of the things I like to spend time doing is studying past investments of other investors to try and understand what they saw in the business, why they invested, and how it worked out. Buffett once said that if he taught a course, it would be “one case study after another”. Last week, I was working on an investment that reminded me of an investment that Graham once referenced. What’s interesting about investment research is serendipity often takes over and you end up reading and thinking about other topics that you never intended to. I’ve found it really effective to allow myself “flex time” within my research schedule to follow those rabbit holes. Sometimes its an industry project, sometimes it leads to studying another business in a completely different area, and sometimes it’s more related to portfolio management or something more general. This post contains some loose-leaf thoughts on the latter category that I wrote down during one of those flex work sessions. I mentioned earlier this year that I wanted to post more “ugly first drafts” - unfinished thoughts from my investment notes. This post is an example of these journal notes. From the thoughts folder in my journal:

I was looking for a case study and ended up rereading Intelligent Investor. I took some notes on Chapter 7 and 15 on portfolio management, and it also got me thinking about similarities and differences between Graham and Peter Cundill (I'll have some more notes to share on Cundill’s book as well, which is another one of my favorite investment books for case studies).

Categories of Investments

In the Chapter 7, Portfolio Policy for the Enterprising Investor, Graham goes over 3 different categories he recommends:

Bargains - stocks trading less than working capital less all LT liabilities (net nets)

Unpopular Large Caps - strong companies during a temporary rough patch

Special Situations - liquidations, arbitrage, workouts

The “Unpopular Large Caps” — high quality companies that are going through a temporary blip in performance — have been a steady source of my own investment results at Saber Capital. So I thought it was interesting that even in Ben Graham's day, this type of approach worked:

“If we assume that it is the habit of the market to overvalue stocks which have been showing excellent growth, it is logical to expect that it will undervalue — relatively, at least — companies that are out of favor because of unsatisfactory developments of a temporary nature. This may be set down as a fundamental law of the stock market, and it suggests an investment approach that should prove both conservative and promising.”

Graham goes on to describe why large caps that are unpopular have an advantage over other stocks in that they tend to have the strength to stay in the game, and when they do recover, the market tends to revalue the stocks rather quickly (see META’s 75% drop and subsequent 300% rise as evidence to this speed).

Perhaps because of the hyperactive nature of our connected world, it probably works even better today. This is a behavioral edge that is not going away, so long as human nature doesn't change.

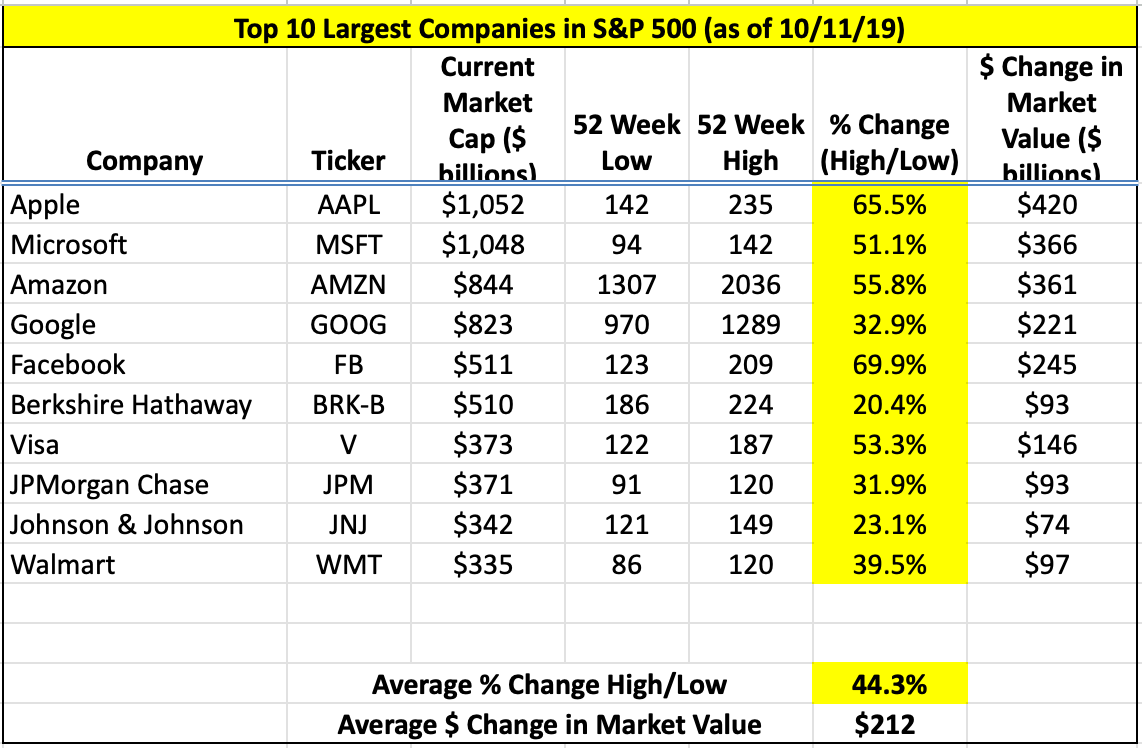

I've long talked about how this approach works by showcasing how volatile stocks are between the 52 week high and low, normally a 50% gap even among the largest stocks in the market. And that's what provides the opportunity. Occasionally (more often than I think people realize), stocks of even the highest quality and most well-followed companies can trade below (sometimes far below) what they're worth.

Here’s a look at a chart that I update every year or so. I included one from 2016, 2019, and 2022 just to show how persistent the fluctuations (and thus opportunities) are:

2016:

2019:

2022:

Just the change in Amazon’s market cap was nearly $1 trillion in this 12 month period: you might argue that neither the high or the low price was the correct value, but one thing I’m confident in is that Amazon’s intrinsic value didn’t change by $1 trillion in just one trip around the sun.

You could repeat this exercise every year, and you'll notice the same thing: stocks fluctuate a lot, even among the largest in the market (even in years where volatility is low like 2019).

Category 2: Time Arbitrage

In the spirit of Graham’s categories, I recently gave a presentation to Saber investors during our latest client Zoom call with an overview of my own three main categories of our own investments: 1) Core operating businesses that we hope can compound value for a decade+, 2) Time Arbitrage (Similar to Ben Graham’s Unpopular Large Caps) and 3) Bargains.

This “Category 2” provides a frequent enough flow of ideas thanks to a very simple fact: stocks fluctuate much more than true business values do.

Patiently building a list of quality, predictable companies, even among large cap stocks, is likely to be a productive exercise as eventually, something on that watchlist will reach a low price that is in fact undervalued, offering high returns from that level going forward.

For my Category 2 type investments, I always invest with an indefinite time horizon (don't buy the stock if you aren't willing to hold it for a decade), but the reality is these category 2's often work out much faster than you might expect. Realistically, I expect to own them for 3-5 years and often the price revalues itself in a year or two, sometimes even less.

These types of investments are really classic value investments, where the entry price (lower the better) makes all the difference. But it's critical to note that you need a quality business with staying power for the market to eventually revalue the shares. In other words, you need a business earning strong returns on equity that can either turn those returns into growth or pay them out as dividends.

I try to focus these category 2 ideas on stocks that have all three of those engines working in concert, which provides 3 separate possible tailwind to returns.

Time Arbitrage: The Greatest Investment Edge

I’ve written about the concept of “investment edge” on numerous occasions (see: What is Your Edge?), and how in today’s world, information has become easier to get and thus more of a commodity. But this information access, along with other technologies, has caused our attention spans to become shorter and shorter, which I think has diminished our patience and our time horizons. We want results now. This has created a “time arbitrage” opportunity, and I expect this will only gain strength as time horizons and patience levels continue to shorten.

Past examples of Category 2 ideas would include Apple in 2016 when pessimism surrounding the next iPhone cycle and worries about Apple’s competition caused the stock to fall below 10 P/E, Verisign when worries about government intervention into its pricing practices caused the stock to fall to multiyear valuation lows, or large banks like BAC and JPM in 2015-2016 when the market was expecting and fearing a difficult economy (and larger loan losses). More recent examples of mispriced large caps might include large cap tech stocks in 2022: AMZN fell 50% in 2022 and rose 80% in 2023, and that was mild compared to what happened at numerous other mega cap stocks. The valuation levels fluctuate far more than business values.

To be clear, there always is a legitimate negative fundamental case to be made when stocks get mispriced, but I think the majority of the time these concerns tend to be focused on the short term. Amazon over invested in warehouse capacity because it overestimated the growth in online retail sales, but was this going to negative impact Amazon’s long-term moat? (I would argue that in one sense it actually further entrenched their moat, making it very difficult for other retailers with lesser capacity to offer the same experience of low cost and speed of delivery: another large online marketplace with ambitions to enter the logistics space ended up throwing in the towel during this period). Sometimes, these short-term difficulties end up being long-term beneficial for the “unpopular large caps”, and the great thing about this category of investment is you get to acquire a stake in these better-positioned large companies when their stocks are depressed.

JPM is recent example of a Category 2 idea as well: the stock traded down under 8 P/E in the summer of 2022 when recession fears were prevalent (similar to what happened in 2016 to bank stocks).

I think Jamie Dimon had some great advice on the right mindset last year when he said (paraphrasing): “in 20 years, the world’s stock market capitalization will be much higher, the assets in the banking system will be higher, corporate earning power will be higher, the dollar volume of merger transactions will be higher, global payment volume will be higher.” The implication is JPM has a durable moat and thus is positioned to take a cut of all of that business. Earnings might decline in the near term, but what matters to business values is the long-term free cash flows that it earns over time.

Dimon’s point: focus on the big picture and don’t worry so much about next quarter. But the stock market worries a lot about next quarter and next year. And this causes lots of volatility in stock prices — much more volatility than long-term business values. Including dividends, JPM is now up 70% from those summer lows of just 19 months ago.

Stock prices fluctuate much more than intrinsic values do. That’s the opportunity that Ben Graham saw many decades ago, and it’s the opportunity that still presents itself today on an annual basis.

This post got long for what I’d like these “ugly first draft” posts to be, so I’ll publish the follow up with his view on diversification and my own thoughts on this aspect of portfolio management later this week.

John Huber is the founder of Saber Capital Management, LLC. Saber manages separate accounts for clients and also is the general partner and manager of an investment fund modeled after the original Buffett partnerships.

John can be reached at john@sabercapitalmgt.com.

Disclaimer:

John Huber and clients of Saber Capital own shares of JPM. This article is for educational purposes only. We make mistakes and cannot make any warranties or guarantees about the performance or accuracy of anything on this site. We are long-term investors who are not concerned with near term results. Please conduct your own due diligence, take your time doing your research and only act when you have developed conviction based on your own understanding and your own work.

Please see full disclaimer here.

Very nice and greatly appreciated.

Keep writing!