The Power of Incentives; SVB and Berkshire

A review of Silicon Valley Bank's capital allocation policies, its cash flow statement, and a case study on the power of incentives

Last month I happened to be reading Berkshire’s 10-k on the day that Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) failed. I intended to write about Buffett’s letter and some general takeaways from Berkshire’s results, but the banking news diverted some of my attention to looking into various bank balance sheets and sifting through the universe of hundreds of bank stocks out of curiosity to see if any babies were getting thrown out with the bathwater. (I joined Jake Taylor and Toby Carlisle on their Value After Hours podcast to discuss a little system I’ve been using as a hack to help organize this research project).

This post initially was going to be a summary of one subtle but important comment from Buffett’s letter that I haven’t seen discussed: his reference to Berkshire’s capital as “your savings” (speaking to his shareholders). This way of speaking isn’t anything new from Buffett, but I got to thinking about this language as I was studying the failure of Silicon Valley Bank.

This post isn’t an admonishment of SVB’s management or its business model, and while there were big mistakes, they did nothing illegal. But SVB is a great case study on the power of incentives, and so it’s worth reviewing.

Charlie Munger says he believes he understands incentives better than 95% of everyone and yet he still feels he underestimates the power of them. Reading Berkshire’s financial statements and comparing them to SVB’s is yet another great example of how incentives drive behavior.

The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank is about three things:

Short-term thinking (incentives to produce profits now regardless of long-term risk); This led to…

Poor capital allocation decisions, which then enabled…

A concentrated deposit base to become problematic

In my view #1 was the real issue. #2 was the result. But #3 only became a problem because of the first two. Many companies have concentrated customer bases and some have even built long-lasting businesses serving just one main customer (contractors for the government, suppliers to Costco, etc…). Concentrated customer bases always have some level of risk, but that risk can usually be managed. Though wood can catch fire, a house made of wood that burns to the ground is usually not the wood’s fault. SVB’s concentrated customer base only became a problem after decisions were made to take a lot of risk tomorrow for a little extra money today. SVB didn’t fail because of the run on the bank. It failed because it wiped out its capital, which then created conditions that led to the run. So what caused the bank’s book value to get wiped out?

Bank Cash Flows

Bank cash flow statements are really interesting to study in recent years because there has been such an inflow of deposits, and the cash flow statement allows us to trace the flow of those deposits to see where they were invested.

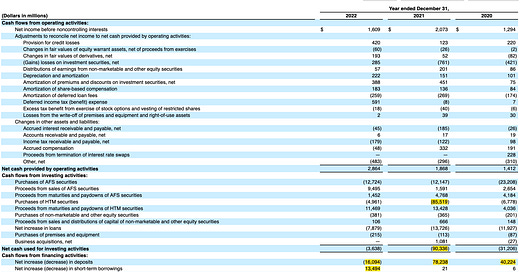

Looking at SVB’s cash flow statements from 2020-2021 shows a whopping $118 billion of incoming cash from deposits and $92 billion of that going into long duration bonds yielding 2% or less:

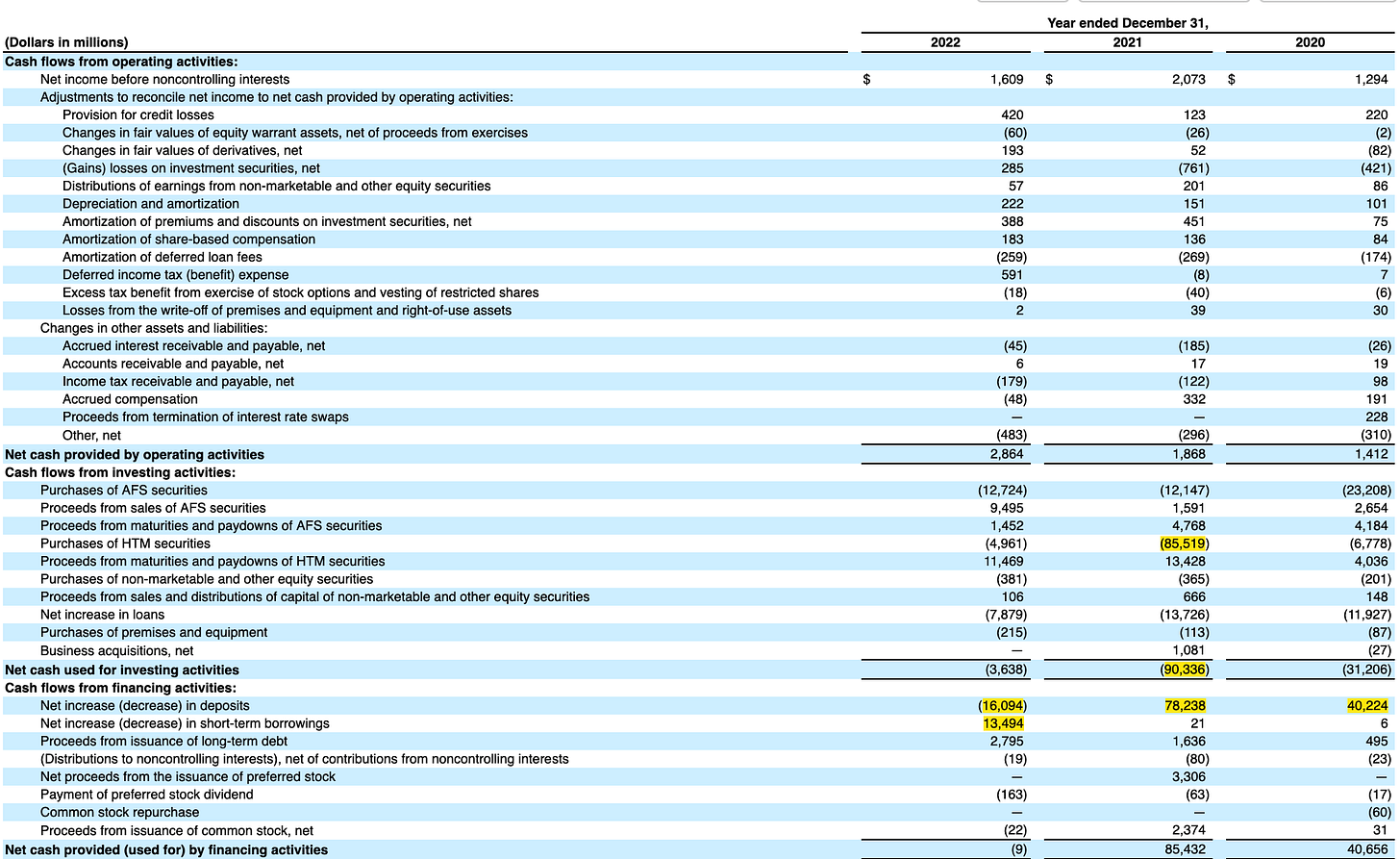

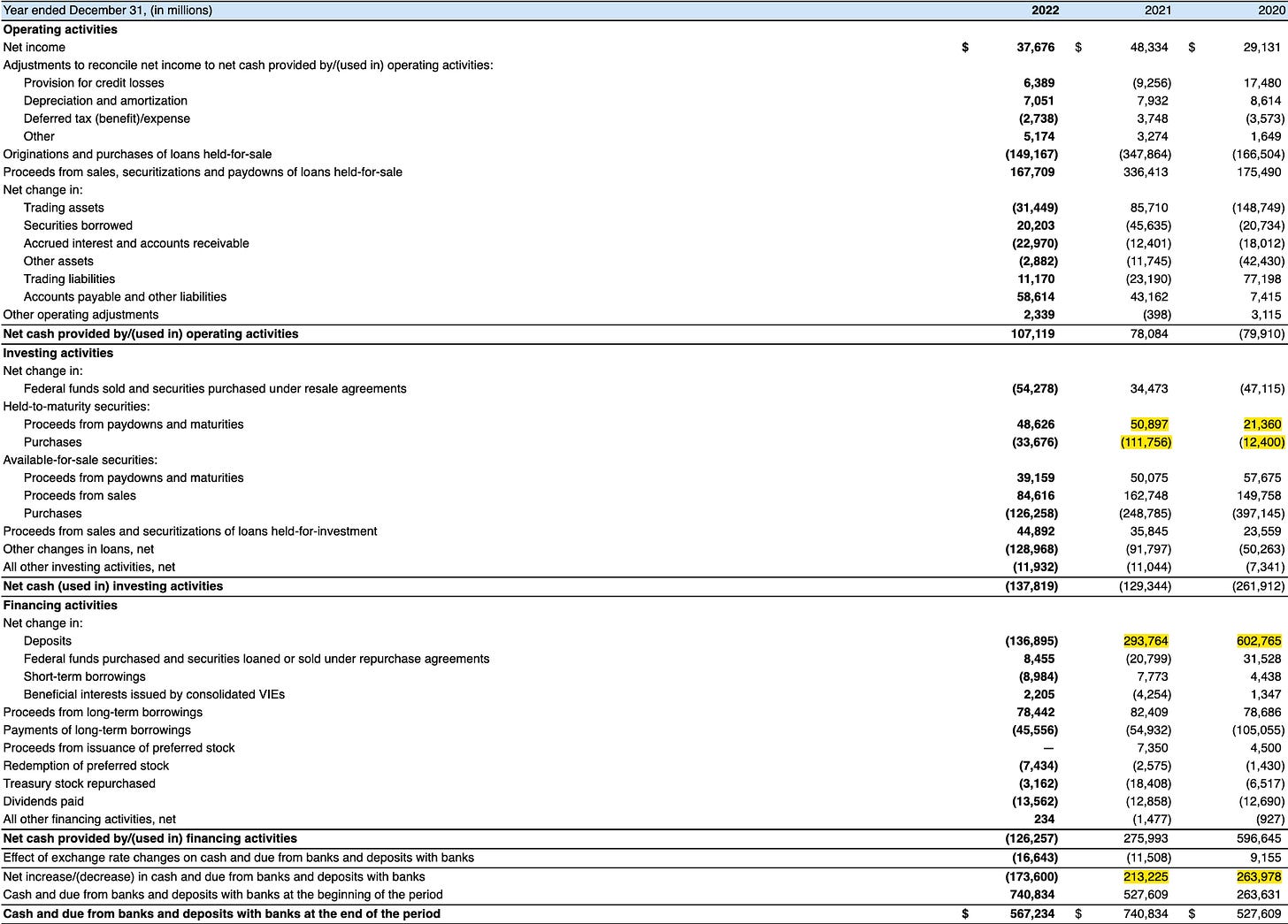

For a 180 degree contrast in the management of surplus of funds, JP Morgan is a good one to study. I’ve reviewed a bunch of bank cash flow statements in the past month, and few have allocated capital as effectively as JPM, which basically saw nearly $900 billion in deposit inflows and kept over 90% of this surplus in cash and short-duration securities, which is a mountain of dry powder that is now being put to work at much higher rates (e.g. their net interest income and pretax profit were up an incredible 50% yoy in Q1).

JPM’s Cash Flow Statement:

Comparing SVB to Berkshire is different; it’s apples and oranges of course. But it still is interesting to observe the differences in capital allocation strategies. With BRK, we see a business that has stubbornly sat on well over $100 billion of T-bills for years, refusing to pay 50 times earnings (which, of course, can’t grow) for a long duration bond that has virtually no chance of providing any positive real return if held to maturity.

SVB Incentives

Reading Buffett’s letter and studying the SVB debacle in the same month laid bare these vast differences in thinking. One management team was focused on making profits this year (without much regard for the safety of the bank a decade from now). The other was thinking decades ahead and working diligently to build a ship that will withstand even the most severe storms imaginable. One team prioritized this year’s earnings at the expense of long-term safety; the other sacrificed this year’s earnings to enhance the long-term safety. One was a management team that gets paid bonuses based on annual profit targets; one was an owner, plain and simple.

It’s talked about how important it is to partner with a management team that thinks and behaves like owners but just as we know the power of incentives but still underestimate them, I think we also underestimate the importance of capital allocation and decisions made with an owner’s mindset.

Buffett sums this up perfectly: “banks can be great businesses if you don’t do something stupid on the asset side”. SVB was a great business until they decided to buy long-term bonds at 50 times earnings (i.e. the price you pay when you buy a bond with a 2% yield). This is extraordinarily risky. There is no credit risk. But that is not the only risk you need to consider when buying a stock or a bond. You also have valuation risk. Microsoft in 1999 had no credit risk (practically speaking). But buying MSFT at 70 P/E had lots of valuation risk. It was a safe business but not a safe investment.

Buying bonds backed by 30-year government guaranteed mortgages carries no credit risk. But they can be very safe investments at one price and extraordinarily risky at another price.

So why did SVB engage in such risky investments? The proxy statement provides the answers. Generally, SVB management was paid bonuses based on achieving certain ROE targets and stock price appreciation. This isn’t unusual and achieving a high ROE is a worthy objective. But the problem lies in the time horizon. The numerator of the ROE (the “R”) is net income. Essentially the management team was incentivized to produce as much profit on their capital as they could this year. This makes the decision very easy on what to do with over $100 billion of new cash from deposits: when left with the choice between 0% and 2%, the latter provides an extra $2 billion in interest income that mostly drops to the bottom line.

To make matters worse, the footnotes deep in the proxy also mention that the compensation committee can make adjustments to these profitability targets for out of the ordinary or “other items that are subject to factors beyond management’s control, such as investment securities gains and losses” (!)

SVB did take advantage and made such adjustments. This is what I really dislike about corporate incentives. It’s heads I win, tails I win also; just slightly less. So adjustments can be made when extraordinary events impact the stock price in a negative way, but management takes full credit for positive surprises (the bonuses were fully paid when the stock soared in 2021).

Again, SVB did not do anything illegal and their incentive structure is (unfortunately) not unusual, but I think the SVB case shows why incentives are so critical to understand at companies you own stock in. This is true for all companies, but especially true for companies in the banking or insurance industries. And it’s why Buffett and Berkshire are so special.

Buffett is willing to sacrifice money now in exchange for more money later. It’s a simple philosophy of maximizing the future cash flow of a business. Most companies aren’t incentivized to maximize future free cash flow. They’re incentivized to make as much as they can this year. Sometimes this short term incentive aligns with maximizing long-term cash flow, but sometimes it doesn’t.

This brings me back to Buffett’s letter and that takeaway I referenced earlier regarding how he thinks about Berkshire’s capital. In the next post (I’m trying to keep my posts short(ish) going forward), I’ll share a few more thoughts on this topic along with some comments on Buffett’s portfolio construction, his coffee can, and some of his all time great investments.

John Huber is the founder of Saber Capital Management, LLC. Saber is the general partner and manager of an investment fund modeled after the original Buffett partnerships. Saber’s strategy is to make very carefully selected investments in undervalued stocks of great businesses.

John can be reached at john@sabercapitalmgt.com.

Short term greedy decisions are painful in the long term!

Thanks for sharing this great article John.

It is great to have you back! Always enjoy your articles and have learned a lot from your writings