Investment Evolution or Flexible Tactics?

A look at Warren Buffett's remarkable investment flexibility and some thoughts on opportunities over the next decade

Bill Belichick’s Patriots won 6 Super Bowls. I view their dynasty as two halves: the first three in 2001, 2003 and 2004; and the next three in 2014, 2016, and 2018. In the first run, they thrived with a great defense that Peyton Manning couldn’t get past in January. The Pats offense was average, and in fact passing yards per game were in the bottom half of the league during two of those first three years and was never ranked higher than 10th. Tom Brady was terrific in those first three championships, but it wasn’t until 2007 when they went 16-0 in the regular season (but didn’t win the Super Bowl) that he emerged as truly the best quarterback in the league, throwing a then-record 50 TD’s.

To me, this marked a sea change in the Patriots offense — from a team that dominated on defense to one that became the most prolific pass offenses the league has ever seen. Brady had many games with 50+ pass attempts, a rarity at that time. They had unique packages that mixed in two tight ends at times, often an empty backfield, great slot receivers like Wes Welker and Julian Edelman, deep threats with Rob Gronkowski and others. Their last 3 more super bowls were won in a completely different way than their first 3.

The team, in both eras, were run by the same coach and the same quarterback, but the strategies were very different.

The Patriots were not a rigid team. They adapted to where the opportunities were.

Buffett’s Strategic Flexibility

I think people overstate Buffett’s “evolution” and assume he once bought cheap stocks and now only buys quality stocks. I think a lot of this is simply due to Buffett’s desire to share credit with Munger, who preferred the quality investments. While I’m sure Munger had some influence, Buffett was buying quality before he met Munger and actually never stopped buying the cheap stocks and special situations when they were big enough to make sense. His North Star wasn’t any sort of quality criteria, it was really just value that he understood.

Here is just a small sampling that shows his flexibility and willingness to be opportunistic:

1950’s: a time known for cigar butts but he also bought Geico, an early stage growth stock

1960’s: Big investments in franchises like Amex and Disney but also special situations like the oil producer arbitrage investments (see the 1962 appendix of his partnership letter for details)

1970’s: Washington Post and Geico (again) but also bought a basket of cheap stocks in the deep bear market (ad agencies, retailers, commodity producers and even some gold stocks — Roger Lowenstein’s Buffett bio references numerous of these bargain purchases)

1980’s: Perhaps his most famous investment, Coca Cola, but he also bought workouts such as bankrupt Texaco bonds and an arbitrage on a timber company called Arcata (a great case study here; some of these workouts resulted in fabulous IRR’s)

1990’s: his portfolio was filled with franchises like WaPo, Coke and Gillette, but he also did opportunistic deals on troubled banks (Wells Fargo hit a rough patch, as did numerous regional banks in the commercial real estate crisis of the early 1990’s); this decade also saw him reverse his long-held investment in Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (showing a remarkable ability to change his mind when the facts changed, despite discussing these investments publicly and owning them for over a decade).

Late 90’s/2000’s: he continued being famous for his large investments in the franchise moats, but he also had some unconventional investments:

He built up a large amount of above ground silver bullion reserves, a small portfolio position but one that is very interesting to study (a great video explaining his very simple thesis here)

He bought bankrupt bonds of telecom companies after the .com bust

He bought a basket of junk bonds, which included bonds of Amazon.

After spending an hour reading the annual report for PetroChina (his own words) and quickly understanding the value of their oil field was 2-3 times greater than the market cap of the stock, he bought the stock (which became a 10-bagger in the next few years)

2010’s: after spending decades talking about how he wouldn’t invest in tech stocks, he bought the biggest tech stock of all (Apple), and it made Berkshire more money than any other investment in Buffett’s career

2020’s: continued remarkable flexibility:

He invested in common and preferred equity of OXY in 2019, sold the common in 2020 during Covid around $15 per share, and then reinvested in OXY just two years later at prices 4x higher, around $60 per share (the OXY investment hasn’t performed well, but it’s an example of his flexible mindset)

He bought his basket of Japanese trading companies, despite a history of not investing in stocks overseas (these investments have performed incredibly well: see post)

Not all of these investments were big winners. My point in highlighting these is just to show that Buffett doesn’t box himself into any style box. He simply wants to find investments that will grow his capital in a safe manner.

Investment Evolution?

I went back and reviewed a few of Buffett’s past investments because I recently joked that I am going through a reverse Buffett evolution that started with great companies and is now moving toward value stocks. But I realized it’s not an evolution. I’m just simply trying to find good investments. My philosophy around value is the same as it was a decade ago when I started Saber.

My goal has always been to invest in stocks that I think will offer 15%+ returns going forward. It’s really that simple. My strategy prioritizes safety of principle. It involves looking for good companies that I understand, and that have what I think are predictable earnings over the next decade, but these can come in lots of different shapes and sizes.

There was an exchange on Twitter with some comments on this subject:

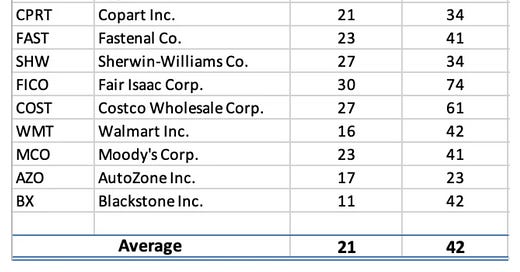

When I started Saber a dozen years ago, great quality companies (today what are commonly called compounders) were all reasonably priced; some were downright cheap. Apple and Microsoft traded at 10 P/E at times. I took a random sampling of my compounder watchlist and glanced at the P/E’s a decade ago and compared to today. These weren’t cherry picked — I picked them out randomly from my quality watchlist:

These are all great businesses, and I’m not suggesting these are all overvalued, but returns going forward are likely going to look much more average than people are used to from this group. If the P/E ratio reverts to just these companies’ own historical averages, it will result in mid-single digit returns even if growth remains at the same level as last decade (a 12% growth rate combined with a P/E that gets cut in half yields a 4% CAGR for the stock over a decade).

The quality of earnings has also changed at some of the big tech companies as they no longer can grow without capital investment. The rapidly rising capex is changing the return on capital profile, and perhaps the growth going forward.

Next Decade’s Opportunities

In short, I think they’ll come from special situations, bargains, and high quality (even if lower growth) companies that spit off cash and are buying back shares.

If you buy a stock at a 15% FCF yield and it is using all of its FCF to buy back shares, you’ll earn a 15% return in the stock without any multiple expansion. If the multiple does expand, the yield will slide lower but you’ll rapidly be advanced a much larger return in a shorter period of time. I think of these stocks as having a call option attached: we make a nice return on the yield, but if the market does revalue it, it could be a very nice return.

How to Avoid Value Traps

The natural question I often get when discussing smaller value stocks is “what about value traps”? This is when capital allocation becomes so critical. There are a lot of value traps, but they almost always fall into one of two main categories:

No cash earnings: The earnings are very low quality (maybe the P/E ratio is low, but the earnings don’t turn into much free cash flow because the business requires a lot of capital: i.e. a low ROIC business)

The solution here is to own businesses that produce a lot of FCF: it’s okay if there is no place to reinvest it, but we want businesses that “drown in cash”, as Charlie Munger put it, not the business like the tractor dealership he once looked at where the earnings all had to be reinvested into buying new tractors each year

Poor capital allocation: The business does generate a lot of cash, but the management is not paying it out to owners and instead retaining it to spend on low ROIC acquisitions or other low ROIC growth projects

Solution here is obvious: focus on management teams that are buying back shares and/or paying dividends and have a simple capital allocation policy that you understand

Of course, any investment can go wrong for many other reasons, but I think if you avoid these two pitfalls, you’ll dramatically reduce the value trap risk.

The reason these stocks are compelling is as follows. I’ve talked about the three engines of value:

Growth

Capital returns (dividends and buybacks)

Change in multiple

A decade ago, many of today’s great compounders were priced around 16-20x FCF. This is roughly a 5-6% FCF yield. And these companies had a long runway to grow earnings at 10% or more. This is an incredible bargain because we got the 5-6% in the form of a buyback and dividend combo, and we got the 10%+ growth on top of this. A decade ago, many of these companies could grow with little to no capital retained, which means we got to take home the earnings and get the growth: eating out cake and having it too.

This formula (let’s say a 5% FCF yield plus 10% growth equates to a 15% per share return before any multiple expansion). A real life example shifted these variables: Apple traded at a 10% FCF yield and was growing at around 5%. People lost interest in Apple because they thought it was mature and slower growing than companies like Amazon or Google. But Apple outperformed them all, partly because it bought back so many shares and started at such a low valuation.

AAPL compounded at over 30% annually after 2016 because the multiple went from 10x to 30x while reducing the share count and modestly growing bottom line. But what I’d like to impress on you is that even if AAPL had the P/E stayed at 10x and never moved higher, the stock still would have returned around 15% annually if they grew earnings 5% and used all earnings to buy back shares (which would mean a 15% or so eps growth).

I like stocks that produce a lot of free cash flow without a need to reinvest because we can earn quality returns without needing the market to revalue our shares.

Today, as the chart above shows, many of these companies trade at a 2-3% earnings yield and while some might still be growing at decent rates, the risk is that either the growth slows down or the multiple normalizes. Either case would lead to average or even poor results for the stocks. The businesses could continue to do very well, but we want low risk, high quality investments. Costco has a great moat and it is a great business, but at the current price, I believe it is a very risky investment, just as Microsoft and Coke were in the late 1990’s.

Today the opportunities are more in the camp of the 15% FCF yield example I outlined above. Cheap stocks that are using their cash to buy back shares. If we get even a small amount of growth, that’s an added bonus. And we don’t need the market to increase the valuation if we buy at such a low starting multiple.

Medical Facilities was a great example of this last year — a very consistent, predictable hospital owner that has made consistent free cash flow each and every year for over 20 years, trading at a 15% FCF yield and using all the cash to buy back shares. It has since sold one of its core assets and gone into liquidation mode (a case where the value to a private owner eventually became the catalyst).

Current examples might be NRP or FCNCA, both great businesses with high returns on capital and quality management teams that understand the intrinsic value of their stock, which both trade at double digit FCF yields.

The next great investments may come from high quality, but will not all come from the stocks that are today defined this way. I think a flexible mindset is required.

In the next post, I’ll highlight a new idea that has been ignored by the quality crowd, but is nonetheless potentially a very high quality investment, perhaps even a compounding machine.

John Huber is the founder of Saber Capital Management, LLC. Saber manages an investment fund modeled after the original Buffett partnerships.

John can be reached at john@sabercapitalmgt.com.

Disclaimer:

John Huber and clients of Saber Capital own FCNCA and NRP. This article is for educational purposes only. I enjoy writing about investments and exchanging ideas with readers, but nothing here should be considered a recommendation. I make mistakes and cannot make any warranties or guarantees about the performance or accuracy of anything on this site. We are long-term investors who are not concerned with near term results. Please conduct your own due diligence, take your time doing your research and only act when you have developed conviction based on your own understanding and your own work.

Please see full disclaimer here.

Terrific piece - love reading your stuff

Thank you John. I really appreciate the effort you put into pen to paper. Always a great, and thought provoking, read.