Importance of ROIC: "Reinvestment" vs "Legacy" Moats

I've talked a lot about the importance of the concept of return on invested capital (ROIC), and how it is a key driver of value in a business. Feel free to go back and read some of those posts here.

This post is something new for BHI: it's a guest post written by my good friend Connor Leonard (see his brief bio at the end of the post). Connor and I live in the same area (Raleigh, North Carolina), and we get together on a regular basis to discuss businesses we follow as well as investment strategy. He and I think very similarly when it comes to investing in high quality businesses that can create significant value over the long-run. Connor is a smart investor, and I appreciate his willingness to be a sounding board for me at times. This post contains his own thoughts (unedited by me) regarding the importance of a company being able to retain and reinvest its cash flow at high rates of return. I think he articulates the concept very well.

Here is Connor's post:

The Reinvestment Moat

Outstanding companies are often described as having a “moat”, a term popularized by Warren Buffett where a durable competitive advantage enables a business to earn high returns on capital for many years[1]. These businesses are rare and form a small group, however I bifurcate the group further into what I classify as “Legacy Moats” and “Reinvestment Moats”. I find that most businesses with a durable competitive advantage belong in the Legacy Moat bucket, meaning the companies earn strong returns on capital but do not have compelling opportunities to deploy incremental capital at similar rates.

There is an even more elite category of quality businesses that I classify as having a Reinvestment Moat. These businesses have all of the advantages of a Legacy Moat, but also have opportunities to deploy incremental capital at high rates.

Businesses with long runways of high-return investment opportunities can compound capital for long stretches, and a portfolio of these exceptional businesses is likely to produce years of strong returns. It will take some work and a lot of discipline to filter down to the true compounding machines, however I will outline what factors to look for and how many of the “bargains” hide in plain sight. The “Legacy Moat”: Businesses with a Legacy Moat possess a solid competitive position that results in healthy profits and strong returns on invested capital. In exceptional cases, a company with a Legacy Moat employs no tangible capital and can modestly grow without requiring additional capital. However because there are no reinvestment opportunities offering those same high returns, whatever cash the business generates needs to be deployed elsewhere or shipped back to the owners.

Think of a self-storage facility in a rural town with a high occupancy rate and little competition. This location may be generating $200,000 of annual free cash flow, a solid yield on the $1,000,000 of capital used to build the facility. As long as they run a tight operation, and a competing storage facility doesn’t open across the street, the owner can be reasonably assured that the earnings power will persist or modestly grow over time. But what does the owner do with the $200,000 that the operation generates each year? The town can’t really support another location, and nearby towns are already serving the storage demand adequately. So maybe the owner invests it in another private business, or puts it towards savings, or maybe buys a lake house. But wherever that capital goes, it likely won’t be at the same 20% return earned on the initial facility.

This same dilemma applies to many larger businesses such as Hershey’s, Coca-Cola, McDonald’s or Proctor & Gamble. These four companies on average distributed 82.4% of their 2015 net income out to shareholders as dividends. For these companies that decision makes sense, they do not have enough attractive reinvestment opportunities to justify retaining the capital. Even though these Legacy Moat businesses demonstrate high returns on invested capital (ROIC), if you purchase their stock today and own it for ten years it is unlikely you as an investor will achieve exceptional returns. This is because their high ROIC reflects returns on prior invested capital rather than incremental invested capital. In other words, a 20% reported ROIC today is not worth as much to an investor if there are no more 20% ROIC opportunities available to direct the profits.

Equity ownership in these businesses ends up resembling a high-yield bond with a coupon that should increase over time. There is absolutely nothing wrong with this, businesses like Proctor & Gamble and Hershey’s provide a steady yield and are excellent at preserving capital but not necessarily for creating wealth. If you are looking to compound your capital at unusually high rates, the focus needs to shift to identifying businesses that also possess a “Reinvestment Moat”.

The “Reinvestment Moat”: There is a second group of companies that have all the benefits of a Legacy Moat, but also have opportunities to deploy incremental capital at high rates because they have a Reinvestment Moat. These companies have their current profits protected by a Legacy Moat, so the core earnings power should be maintained. But instead of shipping the earnings back to the owner at the end of each year, the vast majority of the capital will be retained and deployed into opportunities that stand a high likelihood of producing high returns. Think of Wal-Mart in 1972. There were 51 locations open at the time and the overall business generated a 52% pre-tax return on net tangible assets. Clearly their early stores were working, they dominated small towns with a differentiated format and a fanatical devotion to low prices. Within the 51 towns, I would bet that each store had a moat and Sam Walton could be reasonably assured the earnings power would hold steady or grow over time.

Mr. Walton also had a pretty simple job when it came to deploying the cash those stores generated each year. The clear path was to reinvest the earnings right back into opening more Wal-Marts for as long as possible. Today there are over 11,000 Wal-Mart locations throughout the world and both sales and net income are up over 5,000x from 1972 levels.

How To Identify a Reinvestment Moat:

When searching for a Reinvestment Moat, I’m essentially looking for a business that defies capitalism. Isolated profits in a small market is one thing, but continuing to achieve high returns on incremental dollars for years should in theory not be attainable. As a business gets bigger, and the profits become more meaningful, it will attract more and more competition and returns should eventually compress. Instead I’m looking for a business that actually becomes stronger as it gets bigger. In my opinion there are two models that lend itself to this kind of positive reinforcement cycle over time: companies with low cost production or scale advantages and companies with a two-sided network effect.

Low Cost / Scale: Going back to the early Wal-Mart example, the stores were so big compared to traditional five and dimes that Mr. Walton could sell each item at a lower margin than competitors and still operate profitably due to the large volume of shoppers. The more people that shopped at a given Wal-Mart, or the more Wal-Marts that were built, only furthered this cost advantage and widened the moat. The lower prices enticed more shoppers, and the cycle continues to reinforce itself. So by the time there were 1,000 Wal-Marts in existence, the moat was significantly wider than when there were 51. Other businesses such as Costco, GEICO, and Amazon have followed a similar playbook, creating a “flywheel” that accelerates as the business grows[2].

Example: Sketch of the Amazon Flywheel

Two-Sided Network: Creating a two-sided network such as an auction or marketplace business requires both buyers and sellers, and each group is only going to show up if they believe the other side will also be present. Once the network is established however, it actually becomes stronger as more participants from either side engage. This is because the network is stronger for the “n + 1,000th” participant compared to the “n” participant directly as a function of adding 1,000 participants to the market[3]. Another way of describing this: as more buyers show up it will attract more sellers, and that in turn will attract more buyers. Once this positive cycle is in place, it becomes nearly impossible to convince either buyer or seller to leave and join a new platform. Businesses such as Copart, eBay, and Airbnb have built up strong two-sided networks over time.

Andreesen Horowitz’s example of Airbnb’s two-sided network:

Judging the “Runway” to Reinvest: Many investors focus purely on growth rates, driving up the valuation of a company growing at high rates even if the growth does not carry positive economics. The key to Reinvestment Moats is not the specific growth rate forecasted for next year, but instead having conviction that there is a very long runway and the competitive advantages that produce those high returns will remain or strengthen over time.

Instead of focusing on next quarter or next year, the key is to step back and envision if this company can be 5x or 10x today’s size in a decade or two? My guess is for 99% of businesses you will find that it is almost impossible to have that kind of conviction. That’s fine, be patient and focus your energy on identifying the 1%. Admittedly this is the most difficult step of the process, with many variables and uncertainties. Each situation will be different, but below are items I look for as positive indicators of a long runway and also red flags that the runway is concluding: Positive Indicators: If a two-sided network is consistently increasing key metrics like users or gross transactions but is still a small percentage of the overall market:

Focus on companies with a high “flow through” margin on an incremental user or transaction, which will help the company expand margins as the network grows.

If a company has a structural advantage that leads to a lower cost model than competitors:

This could be a differentiated business model such as selling direct rather than through agents. Or it could be an advantage developed over time such as technology that results in greater automation. The structural advantage has to be difficult for larger incumbents to duplicate.

If a multi-unit retailer currently has less than 100 locations but foresees an end market of over 1,000:

Focus on companies with a consistent, profitable, and replicable model. The company should primarily be “stamping out” the same prototype over and over while producing consistent unit economics.

Red Flags: If a company that claims to have a long runway begins shifting into new or different markets:

If the future is so bright, then why deviate from the plan? The management may already know the runway is limited and is making a pivot.

If management’s definition of the total addressable market (TAM) is suspect:

Some management teams like to throw out a massive TAM number in a slide deck for investors to focus on. Check the underlying source of that number, if their definition is overly broad they may be trying to mislead investors.

If the recent vintages of growth investments are producing lower returns:

If the most recent stores opened are producing lower sales and margins, but cost just as much, the runway is showing some cracks. Many multi-unit businesses begin to show lower unit returns once outside of core markets.

Why Value Investors Often “Miss” the Reinvestment Moats: I believe identifying these businesses with Reinvestment Moats is possible with some work, but many value investors struggle with identifying a “reasonable” price. My theory is that these Reinvestment Moats tend to “hide in plain sight” because most investors underappreciate the impact of compounding. When assessing a quality business, value investors will often point to a P/E ratio over 20x or the EV/EBITDA multiple of 10x+ to show that Ben Graham would surely shake his head in disgust over such a purchase[4].

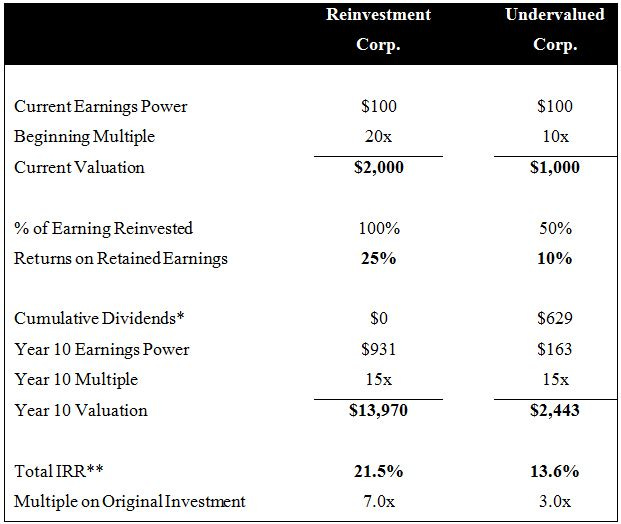

However let’s consider two investments and determine which will yield better results over a ten year horizon. The first business, Reinvestment Corp., has the ability to deploy all retained earnings at a high rate because of the strong Reinvestment Moat it possesses. Of course investors acknowledge this likelihood, meaning the entry price is fairly high at 20x earnings, leading most bargain hunters to pass. On the other hand, Undervalued Corp. has all of Graham and Doddsville in a buzz because it’s a steady business with a nice dividend selling for a bargain of only 10x earnings! Assume that over time both companies will be valued in-line with the market at 15x:

*Assumes all earnings not reinvested are distributed as dividends **Pre-tax IRR, factoring in tax rates will only further the advantage of Reinvestment Corp. This example illustrates a concept Charlie Munger outlined in “The Art of Stockpicking”:

“If the business earns 6% on capital over 40 years and you hold it for that 40 years, you're not going to make much different than a 6% return—even if you originally buy it at a huge discount. Conversely, if a business earns 18% on capital over 20 or 30 years, even if you pay an expensive looking price, you'll end up with a fine result.”

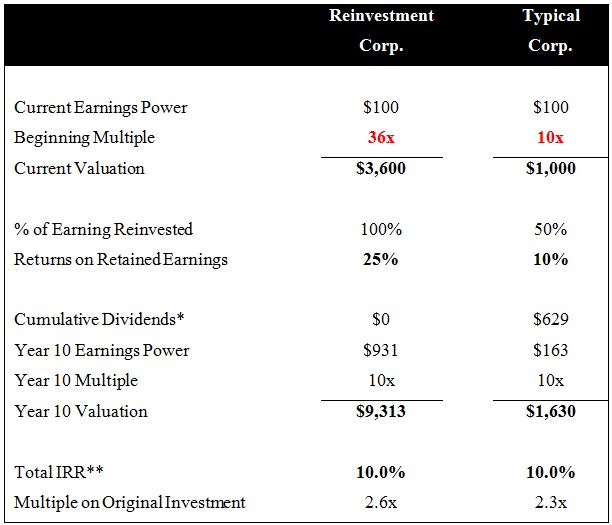

To create an even more extreme example, if you find a business that you believe is capable of earning strong returns over a decade, look at how much you can “overpay” and still earn a return equal to a typical business:

*Assumes all earnings not reinvested are distributed as dividends **Pre-tax IRR Time is certainly the friend of a great business. But does this mean that only businesses with a Reinvestment Moat should be considered for a long-term investment?

Earning High Returns Investing in Legacy Moats: A solid Legacy Moat paired with the right management team and strategy can be a wealth creator for shareholders over many years. In order to accomplish this, the playbook has to change into one more focused on capital allocation, specifically a systematic focus on acquisitions and managing the capital structure. In a sense the management team’s capital allocation prowess must become the Reinvestment Moat.

While the research on the negative consequences of M&A for corporations is extensive, I think there are a select group of management teams that can actually reinvest the company’s capital better than individual shareholders could do on their own. They tend to operate solely within their circle of competence, which is typically the sector where the underlying business resides. With deep industry knowledge, access to deal flow, and the ability to achieve operational synergies, these companies can operate like a private equity fund with permanent capital (and without the fee structure).

Notable examples include TransDigm Group, Danaher Corporation, and Constellation Software. Typically the management team consists of at least one “Operator” and a sole “Allocator”. The Operator is tightly managing the existing businesses to maintain their competitive positions. The Allocator functions more as an investor than a CEO, seeking out opportunities to deploy capital at high rates while also optimizing the capital structure.

For the Allocator the capital structure is another means of creating shareholder value, and it is common to see special dividends, strategic use of leverage, and lumpy share buybacks that only occur when the stock is undervalued.

William Thorndike’s book “The Outsiders” does a fantastic job of detailing these unique management teams with a talent for capital allocation. I’ve found that the best way to find these companies is by reading annual shareholder letters and picking up on certain qualitative patterns. First, a thoughtful and informative annual letter is key because it shows the managers view the shareholders more as business partners and co-owners rather than a pesky group they have to deal with each quarter.

While I prefer to do further research, typically the letter is so insightful to a potential owner that they could make an informed investment decision simply by reading it each year. The letters typically contain terms like “intrinsic value”, “return on capital employed”, and “free cash flow per share” rather than simply discussing sales growth. These businesses tend to view frugality as a source of pride, with the home office setting the tone that each dollar is valuable because it ultimately belongs to the shareholder. If you happen to come across one of these companies, and you think the management team has a number of years remaining with plenty of attractive M&A targets, my advice is to buy the shares and let them take care of the compounding for you.

Summary: Most of the companies that are identified as having a “moat” tend to be Legacy Moats that produce consistent, protected earnings and strong returns on prior invested capital. These are perfectly good businesses and can produce nice returns for investors in a comfortable fashion. However if you aiming to compound capital at high rates, I believe you should spend time focusing on businesses possessing a Reinvestment Moat with a very long runway. These businesses exhibit strong economics today, but more importantly possess a long runway of opportunities to deploy capital at high incremental rates.

If these are hard to come by, the next best alternative is a business with the combination of a Legacy Moat and an exceptionally strong capital allocator. It will take some work and a lot of discipline to filter down to the true compounding machines, however a portfolio of these exceptional businesses acquired sensibly is likely to produce years of strong returns.

[1] If you are new to the concept of “moats”, this video of Buffett speaking to MBA students at the University of Florida does as far better job of describing the concept than I can: https://youtu.be/r7m7ifUz7r0?t=108

[2] The concept of a flywheel is popularized by Jim Collins, you can read more about it here: http://www.inc.com/jeff-haden/the-best-from-the-brightest-jim-collins-flywheel.html

[3] This description of the strength of a network business is taken from venture capitalist Bill Gurley

[4] According to the postscript to the revised edition of the Intelligent Investor, Ben Graham made more money off his stake in GEICO (a true Reinvestment Moat with lost-cost advantages) than he did from every other investment in his partnership over twenty years combined. At the time of the GEICO purchase, Graham allocated about 25% of the partnership’s funds towards the investment.

John's Comment: Thanks again to Connor for putting this guest post together. I think it is a good extension of some of the investment concepts we've talked about here before. For related posts on this topic, please review the ROIC label as well as a recent post I did summarizing the talk that Connor referenced where Buffett does a particularly great job summarizing some of his investment tenets, including the concepts discussed in this post.

Connor Leonard is the Public Securities Manager at Investors Management Corporation (IMC) where he runs a concentrated portfolio utilizing a value investing philosophy. IMC is a privately-held holding company based in Raleigh, NC and modeled after Berkshire Hathaway. IMC looks to partner with exceptional management teams and is focused on being a long-term owner of a family of companies.